I use affiliate links in some blog posts. If you click through and make a purchase, I earn a small commission at no extra cost to yourself. Thank you for your support.

I know my children aren’t alone in experiencing high levels of anxiety, worry and stress around Christmas.

They were adopted at 14 months – but even now, at 6, there are a lot of nerves surrounding any kind of transition or change in routine.

Lots of children find this time of year difficult. Perhaps it’s because they’ve suffered the trauma of being removed from birth family, like ours, or because they’ve suffered a different trauma, possibly around Christmas, or because they have additional needs which make change very hard to navigate.

So what do we do? How can we help our children manage their emotions, navigating together so that they can not only have an enjoyable Christmas, but also develop resources which will help them face anxiety-inducing situations in the future?

Why might adopted children be more anxious at Christmas?

(If you’re reading this with an anxious child who isn’t adopted or fostered then please forgive me for this section, which focuses on adoption, as this is what I can talk about with authority. Feel free to skip ahead to the next section, or you may find something helpful in what I write here which you can adapt to your own situation.)

I’ve already mentioned transitions. Even in the ‘best case scenario’, adopted children will have moved from birth mum to adoptive parent/s in an EPP (Early Permanence Placement, commonly known as ‘Foster to Adopt’). Just this one move will have uprooted a child right at the point their brain was most actively developing, thus putting them on ‘high alert’ when transitions take place.

So, if a child senses that there’s about to be a transition of the seasons, a shift to the normal pattern of life, they may understandably become anxious.

And now think about the reactions of a child who may have experienced many moves – from birth mum, through a variety of foster homes, to an adoptive family or long-term foster family.

For more about the impact of transitions – and why this means that ALL adopted children have experienced trauma – read How Adoption Affects Child Development (Even if they’ve been in Care from Birth).

Another reason for anxiety around Christmas is insecurity, arising from the fact that our children have had to build attachment with us later than normal.

We were designed to build attachment with our primary caregiver from the moment of conception – and we know this from numerous medical studies which confirm that unborn children can hear and recognise their mother’s voice (and father’s, if he is around). In addition, they feel mum’s heartbeat and are soothed by it.

So when those voices and heartbeat seemingly ‘disappear’, and are replaced by others – possibly a foster carer, possibly a variety of medical staff if the baby is in hospital for a stay – a child is confused and not sure who they are supposed to trust now.

We are wired to be dependent on others to meet our needs in those early days – and, unlike animals, our brains do a good deal of developing after we’re born, within a community (see Sue Gerhardt’s excellent book Why Love Matters for the psychology behind this).

Having to break and re-form attachments affects our brains, making us less able to trust the security of a parent’s love and care, however unconditional it is, if that parent was not with us from conception. So times of change like Christmas and other festivals or holidays can bring those feelings of insecurity and distrust to the surface.

For more on attachment, read The Four Types of Attachment Styles Explained.

A third reason might be if a child has experienced upheaval or increased neglect/abuse during previous Christmases.

A child who has spent some time in the birth family, for example, may well have experienced increased shouting, stress and abuse at Christmas. Caregivers may have over-indulged in alcohol and drugs, meaning a more chaotic home than usual. There may not have been presents – or, worse, there may have been promises of great things which never came to light.

Or children may have even moved home around this time of year – like ours did.

The importance of seasons, and how our bodies associate memories with each one, has only more recently become apparent to me. Whether our children have living memories of what happened at Christmas or not is largely irrelevant. As I said to our boys recently, “You don’t remember – but your bodies do”.

In other words, our children may not remember feeling anxious about meeting a new caregiver in November/December – but when the temperature drops and they start hearing Christmas music everywhere, something in them ‘goes off’ and old anxieties rise to the surface.

For an example of how we take our children’s backgrounds into account at Christmas, read What We Teach our Adopted Children About Santa.

What does this anxiety look like?

I’ve discovered that anxiety – in children or adults – rarely looks like cowering behind the sofa, eyes wide and nails bitten. I mean, sometimes it might look like this, but more often than not it is an inner anxiety which can find an outlet in all sorts of behaviours, not all of them obviously stemming from worry.

Some common ones are:

- continual chatter

- continual questions (often repeating the same question many times)

- obsessive, repetitive behaviour (e.g. checking things are closed, off, locked etc)

- increased frequency or intensity of meltdowns, and/or triggered more easily

- increased hoarding of food, nervous snacking etc

- more fidgety, struggling to keep body still

- wetting/soiling themselves

- nightmares, disruption of sleep

- dislike of being alone, more clingy than usual

- behaviours designed to push the parent/carer away (almost as if they are testing the strength of their attachment)

What can we do about it?

There’s a careful balance to be struck, I feel, when our children are anxious.

Imagine being given a can of Coke which has been shaken up. There’s a huge amount of pressure inside that can which needs releasing, so you lever up the ring pull slowly, allowing some of that pressure to be released. Maybe some drink will escape too, but it will be far less messy than if you were to open the can quickly and without due care or attention.

When our children are feeling a lot of big emotions, they’re a bit like that can of Coke. It does them (and us) no good to suppress them.

If I’m being honest, when our kids start talking about Christmas non-stop in November, or bouncing off furniture, or waking early, my natural reaction is to shut them down. I don’t want them peaking too soon, or sky-rocketing their expectations of a day which may then disappoint.

However, to do this doesn’t really do anyone any favours in the long term. My children are likely to become more anxious if I do this, as they wonder why Mum doesn’t want to hear from them, what she may be hiding, whether Christmas is even going to go ahead.

Hard as it is to deal with all the questions, the meltdowns triggered by Christmas talk, or the lost sleep, it is important to acknowledge what our children are communicating to us, so that they feel heard and understood and valued.

Where they communicate to us in words, it is fairly easy to respond with words, by answering a question or acknowledging a statement with a short response and moving on.

Where they cannot use words but use actions, we can respond with empathic commentary: “I think you may be feeling a bit….”, trying to give them words for what they cannot yet articulate for themselves.

So it is important to start to slowly draw back the ring-pull, allowing some of our children’s pressure to be released. Some adoptive/fostering parents even allow children to open Christmas presents in September, or see their gifts before they’re wrapped, where this allays anxiety for them. (Creativity is key when parenting vulnerable children!)

But it is also important not to release the ring-pull too quickly. Where emotions are left unchecked, they run wild, causing damage and destruction to our children’s mental health, our own sanity, and sometimes literally to our homes and possessions. It’s our job as parents to help our children learn to manage these emotions, guiding them to put them in their right place so that the good ones can be enjoyed, and the more negatives ones can be lessened in their impact.

We cannot always control this, of course, but reflecting on how our children are behaving with regards to their anxiety might help us plan in some pre-emptive strategies to support them (and us) the next time they’re particularly struggling.

My first port of call when looking for strategies is the brilliant A-Z of Therapeutic Parenting, which I highly recommend as a quick go-to guide for over 60 types of behaviour. You could also ask on any online forums you’re part of, and if you’re a member of a specialist charity like Adoption UK, you could access the wealth of information and articles available through their website, magazines and emails.

Don’t underestimate either the value of chatting with friends whose children have faced similar challenges. Someone may well have ideas for you to try.

And here’s a practical suggestion that we’re trying out this year:

Christmas Timeline

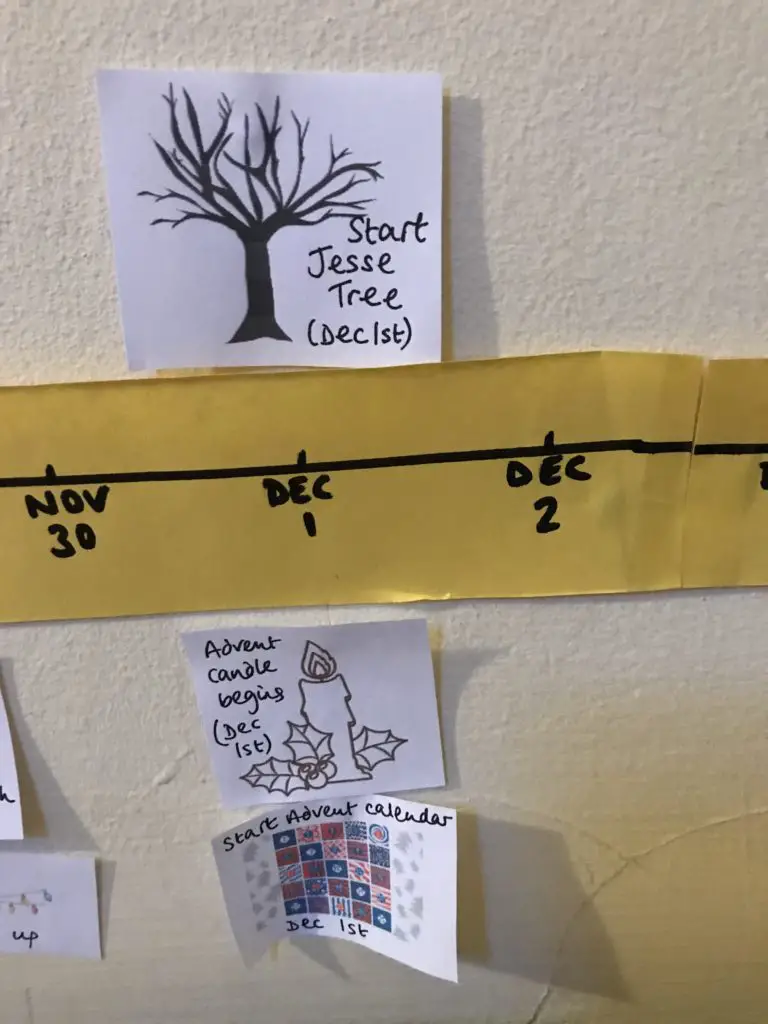

I often make visual timetables for our boys to remind them that there is a plan, that they can feel safe and provided for, and to give them an easy way to know what’s going to happen, so that there are no surprises.

But our boys started to ask questions about Christmas in mid-November, a sure-fire sign of their anxiety, and I didn’t think I could do a 6-week long visual timetable! Firstly, because it would be massive, and secondly, because I simply couldn’t predict exactly when things would happen this far in advance – not least because, at time of writing, we’re not sure when our current lockdown will end.

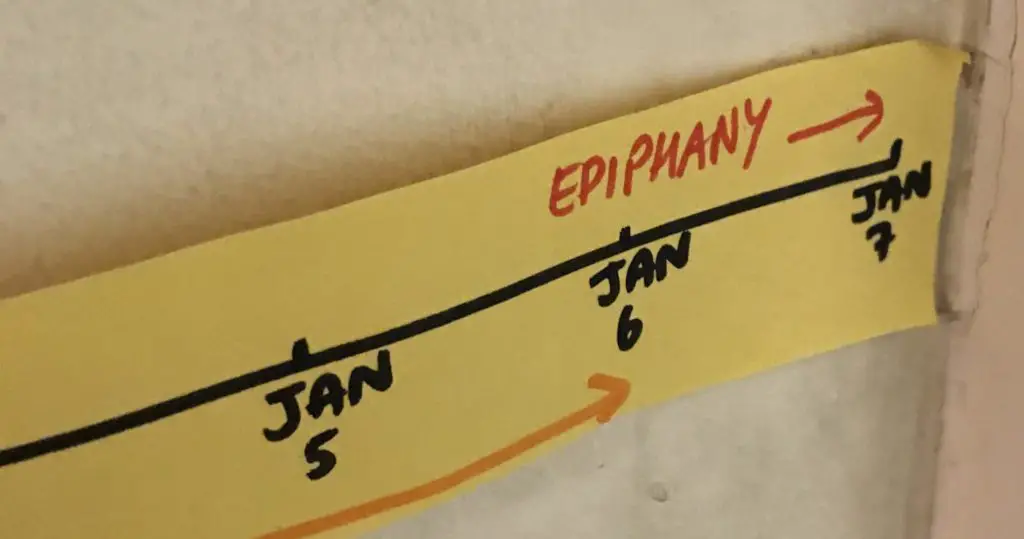

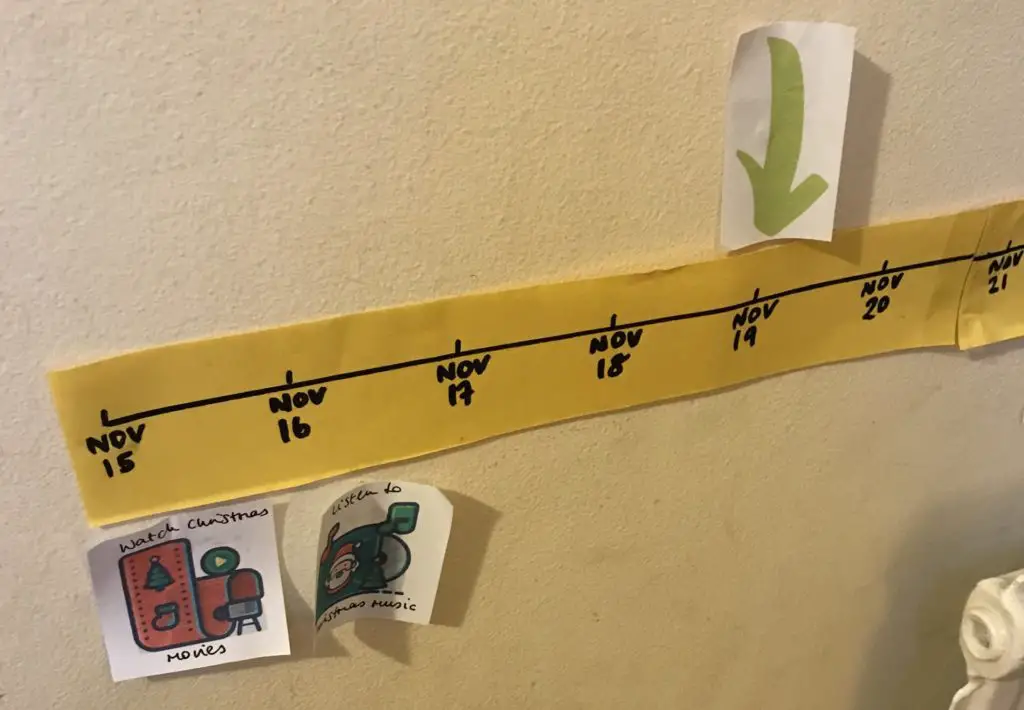

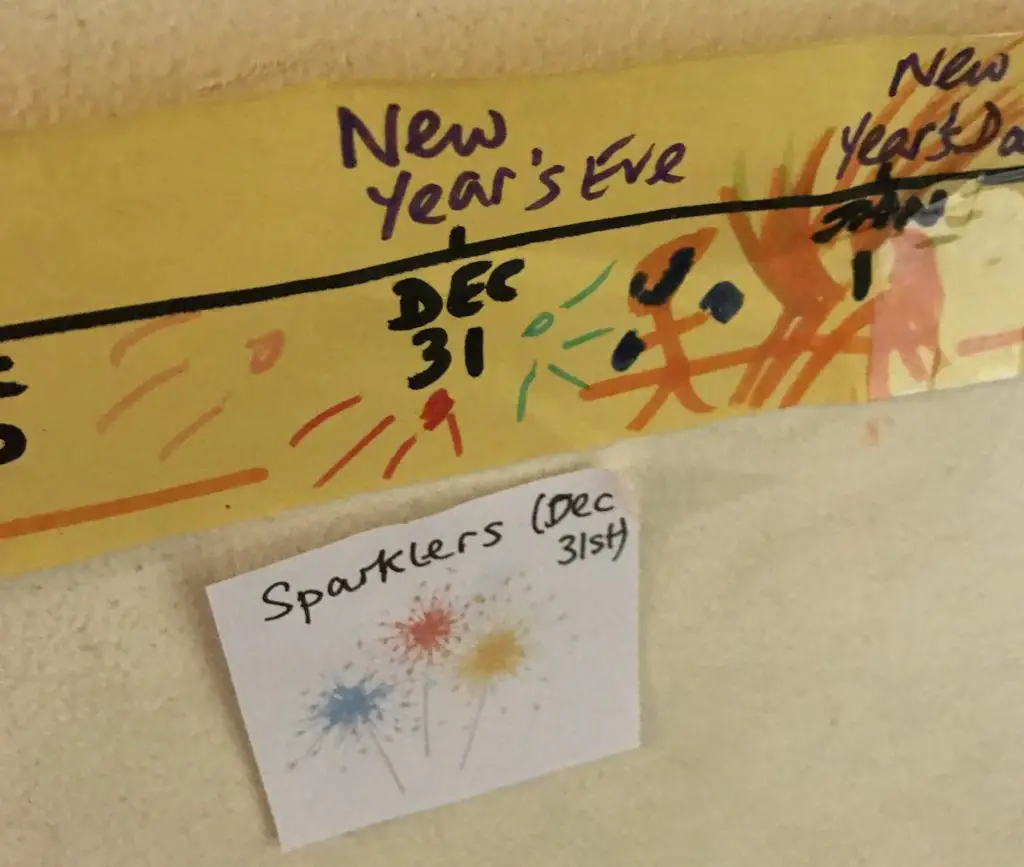

So I took a long stretch of wall, and stuck up a time line which included all the dates between now and January 7th. I wanted our kids to be able to visualise the time between now and when the Christmas season is over, so that they had the assurance that life would continue as normal after the festivities.

I then added little pictures of the various different Christmassy traditions and activities that the boys had already mentioned, so they could see when they were all going to happen – and that they were going to happen at all.

An arrow was blu-tacked above the timeline so that our children could see where we were in the timeline and what event was coming next. We can tell them Christmas is a long way off till we’re blue in the face, but seeing it visualised like this really helps them to understand.

(You’ll notice here that we’re already allowing Christmas movies and music – an example of allowing a bit of the Christmas pressure to come out!)

The beauty of this timeline is that events can be added as they crop up (e.g. school Christmas dinner, which has been announced this week), and we can easily move things around if plans change.

Our kids have spent a lot of time this week looking at the timeline and counting the days to Christmas (another bonus – including every date makes it very easy to do this!), and it really has helped in giving them an outlet to think/speak about Christmas, but without their anxiety overpowering them.

You can grab your own set of these visual timeline cards in my Christmas Printables Bundle:

Over to you – what strategies or tips do you have for helping children to manage their emotions around high days and holidays?

Thank you so much for this! Although we already understand some of the anxieties our 4year old experienceds at Christmas, it is a great article to pass on the her nursery. Our daughter was born in October, went into Foster Care a month later and came to us at 12months old. She is also more likely to become ill during this time of year. Yes, lots of changes in her behaviour at this time of year, disrupted sleep, clingyness, lots of questions in order to seek reassurance, etc. Love your use of the Coke bottle metaphor, really helps us explain to others why she needs a slightly different approach to “getting ready for Christmas”

Thanks again!

Hi Claudi, thanks so much for your comment! Yes you’re right, sometimes nursery/school staff can be less informed about trauma and attachment needs. I hope this blog post helps to explain things a little to them, so that they can help your daughter to thrive xx